Why eyJ excites me

Often when I come across web services and applications with some sort of interesting system, I start questioning how they work. Peeking into devtools and intercepting requests can reveal a lot, but understanding the payloads is just as crucial. In this post I’ll talk about an interesting data encoding format I came across while looking into the Leave Home Safe application, and how I recognized it!

Representing text in computers

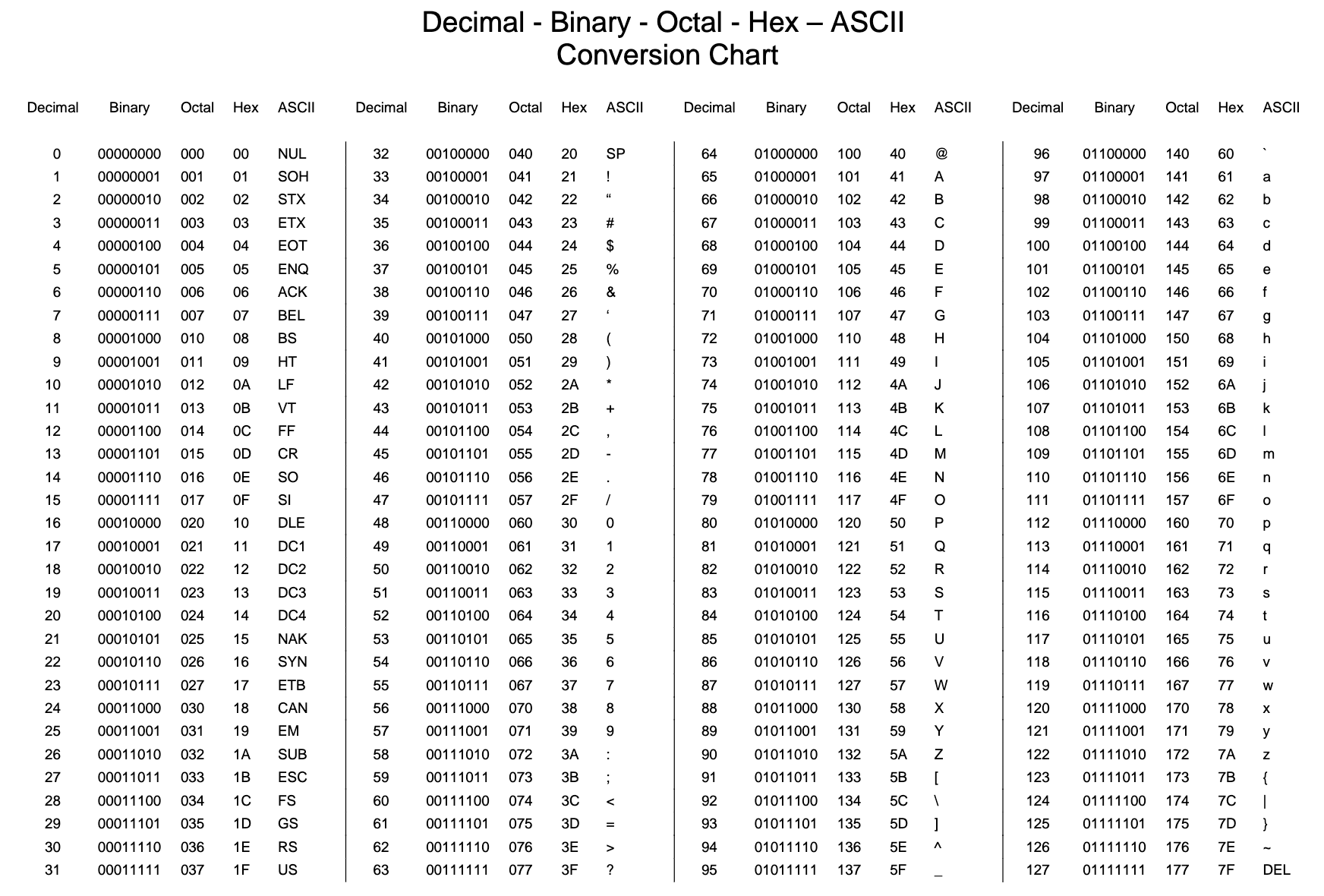

There are various schemes to represent characters as bits so that a computer can understand them and humans can read them, such as ASCII and UTF-8. Most systems today use UTF-8, where all the common english characters and most “keyboard symbols” can be represented in a single byte, or 8 bits.

For instance, the letter ‘A’, is a single byte - 0x41, which in binary would be 01000001. Similarly the byte sequence 0x41424344 would be, as UTF-8 characters, ABCD.

A single byte though, could hold 256 different values (0-255), not all of which map to a printable character. In fact, since UTF-8 is a variable length character encoding scheme, some bytes signify that to decode the bits to a printable character, both that byte as well as the next must be read and mapped. For instance, two bytes form the latin capital letter “Æ” - 0xC386

In the Node.JS REPL we can directly decode bytes as UTF-8. In this example you can see the neither the bytes 0xC3 nor 0x86 are printable characters (The square / question mark is how most browsers render non-printable characters).

> Buffer.from([0xC3]).toString()

'�'

> Buffer.from([0x86]).toString()

'�'

> Buffer.from([0xC3, 0x86]).toString()

'Æ'

Representing binary as printable text

UTF-8 gives a way to encode characters as one or more bytes, so they can be passed around different modes of communication and be rendered at the end, provided the receiver knows to decode the byte stream as UTF-8. There is also another set of encoding schemes used to represent arbitrary binary data as printable text, usually within the 7bit ASCII set.

One such popular encoding scheme is base64, which is widely used to represent binary data as text on the internet. For instance images are often included as base64 strings within an HTML document, which can be decoded by the browser into the binary.

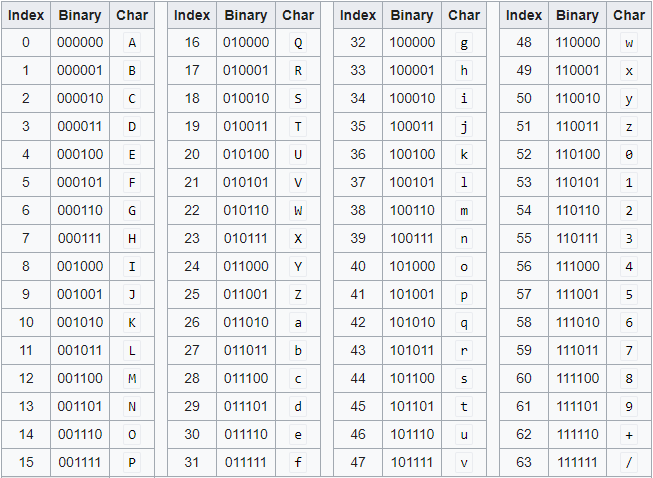

Base64 works by using 64 orintable characters to present 64 different values, from 0 to 63. You may notice that 64 is equivalent to 2^6 - this is no coincidence, each of the 64 characters represents a unique sequence of 6 bits. Below is a base64 table:

Representing text… as binary… as text??

On the web, often simple looking data structures that contain information can actually be too complex to pass as is. This is because they may contain sumbols or such that would need to be escaped when being sent as text. However another solution is to treat the original data as a raw sequence of bytes, and then encode them using a scheme such as base64.

If the data structure is printable text, then the UTF-8 byte sequence can still be converted to base64 to further limit the character set - this is often useful when passing HTTP headers, for instance.

Let’s decode some base64, ey?

So, why does eyJ excite me? Well, let’s try decoding some base64!

I will decode the string eyJK , which I admit, is carefully chosen, but I will warrant my enthusiasm with some probability at the end!

From the base64 table, if we convert each base64 character to its bit pattern, we get 24 bits:

|e |y |J |K |

|011110|110010|001001|001010|

Splitting these 24 bits into groups of 8, we get 3 bytes:

|01111011|00100010|01001010|

|0x7B |0x22 |0x4a |

What’s special about these three bytes? Well, to me, the first two are enough! Let us decode them assuming UTF-8:

> Buffer.from([0x7b, 0x22]).toString()

'{"'

It’s slightly hard to tell since the node REPL wraps the result in single quotes, but the two bytes represent the string {" . If by now you’ve not realized what I’m getting at, perhaps you need to read up a bit on JSON!

Why eyJ works

Some of you may have realized by now - the starting characters for a JSON object - {" , are two bytes, and need to be represented by 16 bits. However eyJ is actually 18 bits. Are the last two bits arbitrary? Would I, K or L, which share the same first four bits, be equally good? The short answer is not really, and the explanation is quite interesting, I think.

To recap, the first 16 bits are fixed for the string {", and the last two can be variable - 00, 01, 10 or 11. If the third character is J, that means the last two bits would be 01. Why is this what I am looking for? Well, the start of a JSON object is meaningless without any data inside it - and for that you need keys! While as per the JSON spec, they key could be literally any unicode sequence (except some fancy backslash escape stuffs), it is almost always going to be english characters, for ease of development. (Note - the same is not true for the value!)

Since after {" in a JSON object, the next character is expected to be an english character, we can restrict the bit pattern to the first two bits needed to represent an english character as a byte. Luckily for us, both the lowercase and upercase english alphabet set must begin with the bits 01 (refer to the ASCII table above) - this means that J is the most probable base64 character when representing the start of a JSON object!

And for this reason, eyJ is the pattern that excites me ;)

So…. Leave Home Safe?

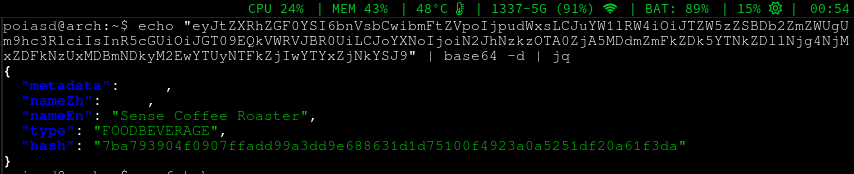

Right. That app. I am planning a whole post about analysis on it, however let’s take a sneak peek into the base64 aspect of it! The QR codes that we need to scan with the app contain a text payload, here is one for my favorite coffee shop:

HKEN:040wdGDheeyJtZXRhZGF0YSI6bnVsbCwibmFtZVpoIjpudWxsLCJuYW1lRW4iOiJTZW5zZSBDb2ZmZWUgUm9hc3RlciIsInR5cGUiOiJGT09EQkVWRVJBR0UiLCJoYXNoIjoiN2JhNzkzOTA0ZjA5MDdmZmFkZDk5YTNkZDllNjg4NjMxZDFkNzUxMDBmNDkyM2EwYTUyNTFkZjIwYTYxZjNkYSJ9

Of course this string isnt base64 directly, for one, a colon (:) is not a valid base64 character. Trying to decode the string immediately following the colon as base64 also fails. What gives? Well, I’m not sure yet as to what it is, but there seem to be 9 characters after the colon that are potentially a checksum of sorts? Or well, something. But after that we can see eyJ - the start of a JSON object in base64!

Decoding the remaining string gives us something quite nice:

ho ho ho! The data for the location which is used by the Leave Home Safe App. The name is already there - thats why it doesn’t need network access! Anyway more on that later… Thanks for reading! If you have questions I’d love to hear from you. You can contact me via email, and please use my PGP key to encrypt all communications.

Questions?

I would be happy to answer any questions you have! You can contact me via email, and please use my PGP key to encrypt all communications. (Backup E-Mail (PGP Key))